DUMBO’s 92 Plymouth Street once served as a boiler house for a neighborhood paper-box company. Now, the immense space houses Smack Mellon, a not-for-profit art gallery.

“We show artists that are under represented, and who don’t get enough recognition,” says Executive Director Kathleen Gilrain. “It’s our choice and mission.”

Smack Mellon moved to Plymouth Street in 2005, but it’s not a newcomer to the art scene. The gallery opened in 1995 as a home for visual artists and musicians. Since then, it has launched the careers of artists such Patty Chang, who has shown at the Guggenheim museum, and Jean Shin, whose work is on display at The Museum of Art and Design.

Smack Mellon selects a group of artists from hundreds of applicants for its one-year residency program, providing each with individual studios below the main gallery, along with computer workstations and a workshop equipped with general, metal and woodworking tools. The 2008-9 term finishes March 31. Here’s a look at how this year’s residents have been making their mark.

– Nicholas C. Martinez

Recapturing ‘Kindness and Imagination’

In a densely decorated studio, Emcee C.M. Master of None showcases his vision of “transforming the world through play” while the metallic chiming of monastery bells plays on an old record player. His displays – a chaotic mix of photographs, prints, playing cards, hand-drawn posters and found items like a dead tree – embody the artist’s mission to get anyone and everyone involved in the creative process.

A sample of Emcee C.M. Master of None's work. (Photo: Amber Benham)

His collaborative works include projects like the Cloud City parade, in which participants – dressed like clouds and armed with spray bottles – imagined a utopia free from “the oppression of predictable weather patterns.” Other projects, like planting libraries on street corners, are part of his plan to “recapture kindness and imagination, which are these childhood virtues that seem to be hard to hold onto.”

– Amber Benham

Challenging Fairy Tale Stereotypes

Chitra Ganesh looks at Cinderella and Alice in Wonderland much differently than most of us. The cartoonish drawings, paintings and digital collages that line the walls of her studio challenge these stories’ violence and stereotypes against women, and what she calls “that whole virgin-whore” dynamic.

Ganesh’s inspirations range from Hieronymous Bosch to Kiki Smith. In a holograph-like lenticular print, she has layered several close shots of the face of a 1970s Bollywood heroine, lending the image a sense of movement: viewers alternately see her beautiful face and her frightening skull.

Many of Ganesh’s works depict women reconstructed; one drawing shows a woman’s head attached to a hand instead of a body. By using popular imagery to address complex ideas, she hopes her graphic comic style will attract a wide audience.

– Marcella Veneziale

Art and All That Jazz

Jennie C. Jones’ project The Walkman Compositions examines the relationship between art, music, and black history in an improvisational style akin to jazz. Using media forms ranging from collage and ink pieces to small sculpture, Jones’ work has a minimal aesthetic rich in visual appeal and symbolism.

What she calls “clusterfucks” are bunches of ear buds tangled together, hanging from a lone plug that extends up into the wall. One clump, coated in pyrite, or fool’s gold, is a knock at the music industry. For her “Breathless Series,” she wound audiotape from Kenny G’s “Breathless” cassette around 16-inch-by-20-inch pieces of white paper. Jones says it’s a “reclaiming” gesture, giving Kenny G’s music free, organic, avant garde roots – all the things it stripped away from jazz.

– Collin Orcutt

Dissecting ‘The Good Life’

Columbian artist Carlos Motta hit the streets of 12 Latin American cities equipped with a video camera to record responses to questions about U.S. foreign relations with Latin America. Between 2005 and 2008, Motta took the pulse of more than 360 pedestrians and recorded their perceptions of democracy, leadership and governance.

Residents of Buenos Aires, Guatemala, La Paz, Panamá, and many other cities appear in his video installation, The Good Life at Smack Mellon, where he is both an exhibiting and a resident artist. The voices from the video monitors mounted on a four-part, two-tiered wooden structure sound as if they are in conversation with one another and with the viewer. Motta’s installation is part of a larger project comprised of an Internet archive of videos. As he explains on his website, “The Good Life modestly looks to re-claim my status, as well as that of those around me, as conscious, informed and critical citizens and subjects.”

– Maya Pope-Chappell

Taking a Panoramic View of Photography

Kwabena Slaughter‘s art asks, “If photography had grown from a different aesthetic tradition, what would it look like?” The 32-year-old Chicago native is taking photography to a new level with what he calls “panographs.”

“The design of the camera really stopped when it was good enough to be reproduced,” Slaughter says. “I wanted to see how much the device affected the image being made.”

Kwabena Slaughter (Photo: Nicholas C. Martinez)

By moving film through the camera while the shutter is locked in the open position, he elongates the exposed image to cover an entire roll of film, enabling him to shoot pieces up to 100 feet long. Slaughter has been working in this medium since 2003, inspired by Japanese scroll painting and the theory of camera as painting-aid. Instead of creating images using new digital cameras that claim to capture sweeping 180-degree views, Slaughter is kicking it old school.

– Kaili Boyd

Turning Sweat Equity into Art

“As an artist, I like to create situations for people to come together and to have an encounter,” says Ginger Brooks Takahashi.

A sweat lodge in Michigan was the inspiration for her final project at Smack Mellon.

While visiting a women’s separatist community, she sat with a group in a communal-built outdoor sauna and found it to be “a true Utopia.”

Hence the pine-scented mound of branches blanketing one side of her studio space and the cone-shaped ceiling-high teepee made of sticks and tree stumps in the opposite corner. Standing on the Brooklyn Bridge just after Christmas, Takahashi was struck by all the discarded Christmas trees she saw on the streets below. She gathered as many as she needed and cut them up to build the piece, which she will eventually cover with the greenery.

“I have a vision of moving this to a friend’s backyard,” Takahashi says. “We’ll sit inside and heat the rocks and herbs, pour water over them and work up a sweat together.”

– Lois DeSocio

A New Look at Bert Williams

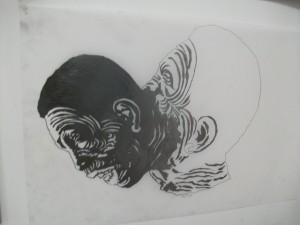

Wayne Hodge watches a barrel-chested Bert Williams take the stage on a screen. The Antigua-born Vaudevillian is wearing coal-black makeup, with round white eyes. In tribute, Hodge put on his own blackface act in “The Original Comedy,” a play that appears on a still photograph.

Alongside the screen, pitch-black silhouettes of grotesque blackface masks hang on the wall. “They are still used today at carnivals,” says Hodge, whose interest in such masks led him to look deeper into the curious history of Afro-Germans.

Influenced by expressionist films of the 1920s, Hodge’s stage performances and artworks tackle racial stereotypes and remind viewers that even in a demeaning makeup, Williams opened the door on Broadway for other black actors. “He was the first black on Broadway,” Hodge says of Williams. “He was the highest paid entertainer in his day.”

–Sergey Kadinsky